Book Excerpts

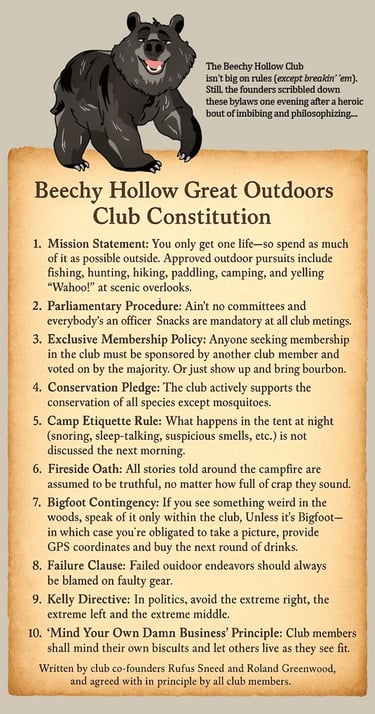

Club Constitution

Prologue to the novella-length story,

The Evil Psychic Mule of Devil Ridge

(Excerpted from Tales of the Beechy Hollow Great Outdoors Club)

They say Crazy Zeke wasn’t always crazy. Back in the day, he was a strong hand in the coal mines of southern West Virginia, swinging a pick with the best of them.

Then came the cave-in. Roof fall at Shaft Number Nine down at Grubb Hollow. Twelve miners killed. Zeke would have been the thirteenth, but when rescuers dug him out, he was still breathing—barely. He survived, but was never the same.

He swore off coal and drifted west to chase gold. When he came back years later, he was lean, sunbaked, and still burning with gold fever. He panned the creeks around New River, then built a cabin on Devil Ridge and started poking around old coal shafts.

Prospecting for gold in West Virginia wasn’t completely crazy. While largely forgotten today, the country’s first gold rush was in southern Appalachia. That lasted until the California Gold Rush lured all the prospectors west.

But if Zeke ever found gold in any quantity, no one knew about it. He became a recluse, wandering the creeks and hills talking to himself, muttering about claim jumpers. The stories grew from there. Hunters who ventured up his way said he had a crude sign painted on his cabin door: Git kot git shot.

Then one day, he vanished—no trace, no body. Some say he went back out west. Kids tell stories around campfires about Crazy Zeke still out there hiding in the hills.

Most stories claim Zeke was the only survivor of Shaft Number Nine, but that’s wrong. He was the only human survivor. Just before the collapse, a mule broke free of its harness and ran out of the mine. By then, mules had mostly been phased out, but some small operations still used them to pull coal carts. This mule was said to stare at people in ways they found unsettling. After the disaster, it escaped into the woods, where it was spotted occasionally by hunters or folks digging ramps or ginseng.

Mine mules lived grim, confined lives. Once taken underground through special entries, or lowered by slings down narrow shafts, many would never see sunlight again. They labored for long periods, slept in stone stalls and ate grain brought by rail. The darkness and toil slowly changed them. Some said the mules learned to see in the dark. Others claimed the rock spoke to the critters. “That one hears the stone talkin’. I ain’t goin’ where it leads.”

Old-timers of a more superstitious bent said it wasn’t the rock, but something older than stone, older than coal, something that hated the light. It seeped up from the cracks in the earth and whispered secrets to the animals through bedrock.

And the mules, buried so long in the dark, were empty enough to listen. . . .

Copyright © 2025 by Robert E. Saunders

Connect

Join our newsletter for updates and news.

subscribe

res@robertesaunders.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.